当前你的浏览器版本过低,网站已在兼容模式下运行,兼容模式仅提供最小功能支持,网站样式可能显示不正常。

请尽快升级浏览器以体验网站在线编辑、在线运行等功能。

2702:Can a Complicated Program Go Wrong?

题目描述

Software systems in practice can be very complicated, particularly when they are implemented by distributed, networked, multi-threaded, or concurrent techniques. Debugging these systems is hard, because the systems can go into one of so many possible states. Image that in any time, you take a snap shot of the memory (or variable values) of a program. That is a state of the program. Typically, a program executes a statement to move from one state to another.

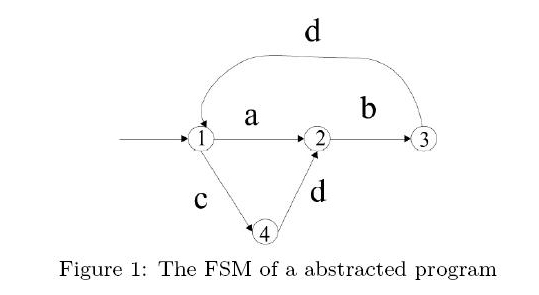

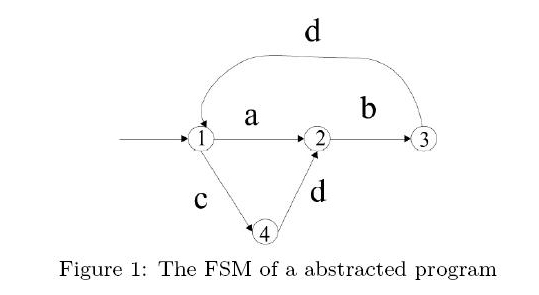

Suppose we want to check if a program can behave correctly. We first abstract a program into a finite-state machine (FSM). An FSM is shown as Figure 1. A state is illustrated as a circle. A starting state is pointed by an edge without symbol and source state. The edge symbols a, b, c,d represent the actions which cause the state transition.

Theoretically, the program contains the following behaviors

abdabdabdabd.....

abdcdabdcdabdcd....

cdbdcdbdcdbd......

abdcdbd.........

..................

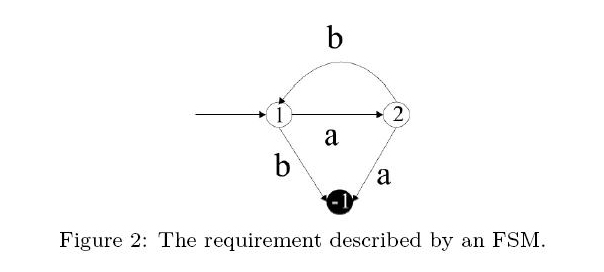

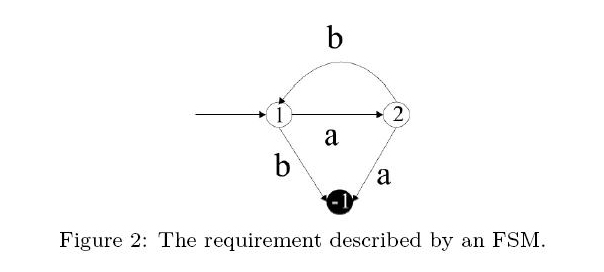

There are more infinite sequences to go on. Each infinite sequence is a possible run of the FSM. The set of these infinite sequences is called the behaviors of the program. Sometimes, we want to check if a program can go wrong in any of these possible behaviors. For example, suppose action a is to request a memory and b is to release a memory. We may want to make sure a always occurs before b in any run and b should not occurs without a. We can describe this requirement by an FSM as well (see Figure 2). The black state represents a trap state (numbered -1), a state which once a run goes in, it cannot go out. When a run enters a trap state, the requirement is violated.

Given an FSM and a requirement (both described by FSM), your goal is to write a program to answer if the requirement is satisfied by all the possible behaviors of FSM or can be violated by at least one run. For example, FSM in Figure 1 has a run abdcdb..... which violates that requirement FSM. The second b appears without an a occurs first. The requirement is violated.

Suppose we want to check if a program can behave correctly. We first abstract a program into a finite-state machine (FSM). An FSM is shown as Figure 1. A state is illustrated as a circle. A starting state is pointed by an edge without symbol and source state. The edge symbols a, b, c,d represent the actions which cause the state transition.

Theoretically, the program contains the following behaviors

abdabdabdabd.....

abdcdabdcdabdcd....

cdbdcdbdcdbd......

abdcdbd.........

..................

There are more infinite sequences to go on. Each infinite sequence is a possible run of the FSM. The set of these infinite sequences is called the behaviors of the program. Sometimes, we want to check if a program can go wrong in any of these possible behaviors. For example, suppose action a is to request a memory and b is to release a memory. We may want to make sure a always occurs before b in any run and b should not occurs without a. We can describe this requirement by an FSM as well (see Figure 2). The black state represents a trap state (numbered -1), a state which once a run goes in, it cannot go out. When a run enters a trap state, the requirement is violated.

Given an FSM and a requirement (both described by FSM), your goal is to write a program to answer if the requirement is satisfied by all the possible behaviors of FSM or can be violated by at least one run. For example, FSM in Figure 1 has a run abdcdb..... which violates that requirement FSM. The second b appears without an a occurs first. The requirement is violated.

输入解释

The test file begins with a number n, n <= 10, the number of test cases. In each test case, there are two FSMs to read in. The first FSM is the program and the second is the requirement. Each FSM begins with a line of three numbers s e i, where s is the number of states, e is the number of edges. 2 <= s <= 500 and 2 <= e <= 2000, and i is the starting state of the FSM. Following the three numbers are e lines of edges. Each edge begins with starting state, action symbol (a–z), and the destination state. A trap state is represented by '-1'. A blank and empty line is used to separate the data of two FSMs.

输出解释

For each test case, please output "satisfied" if no runs of program violate the requirement. Output "violated" if at least one run can go into a trap state.

输入样例

2 4 5 1 1 a 2 2 b 3 1 c 4 4 d 2 3 d 1 3 4 1 1 a 2 2 b 1 1 b -1 2 a -1 4 5 1 1 a 2 2 b 3 1 c 4 4 a 2 3 d 1 3 4 1 1 a 2 2 b 1 1 b -1 2 a -1

输出样例

violated satisfied

提示

You need to figure out a way to "merge" two FSMs, i.e., to obtain a new FSM which has composite behaviors of the two FSMs. Next, search for the trap state in that composite behaviors if any.

最后修改于 2020-10-29T06:40:00+00:00 由爬虫自动更新

共提交 0 次

通过率 --%

| 时间上限 | 内存上限 |

| 1000 | 65536 |

登陆或注册以提交代码